A Book Review: “Of Boys and Men” By Richard Reeves

In case you missed some recent articles:

- Jesus Targeted Hearts, Not Systems

- The Freedom of Limits

- Single Awareness Day

- I Forgive You

- Information Correctly Examined

Richard Reeves’ Of Boys and Men enters into a cultural conversation that has long been muted, if not actively resisted… the struggles of men and boys in modern society. The book, in many ways, is revolutionary for its willingness to state the obvious. There is a crisis among males. Educationally. Psychologically. Socially. Reeves’ arguments invite both appreciation and scrutiny, particularly when viewed through a psychological lens. While he successfully highlights the scope of the crisis, his solutions raise important questions about the interplay of biology, culture, and politics in male development. Here, I propose both praise and criticism of this book.

Institutionalized Developmental Delay

Reeves begins with education, pointing to staggering trends that show boys falling behind at nearly every level of schooling. Fewer men enroll in and graduate from college. They remain at the highest risk of dropping out compared to any other measurable group. Some of this decline has been masked by well-intentioned initiatives aimed at supporting women in higher education. But Reeves notes the imbalance of scholarships and assistance programs that overwhelmingly (and sometimes only) target women.

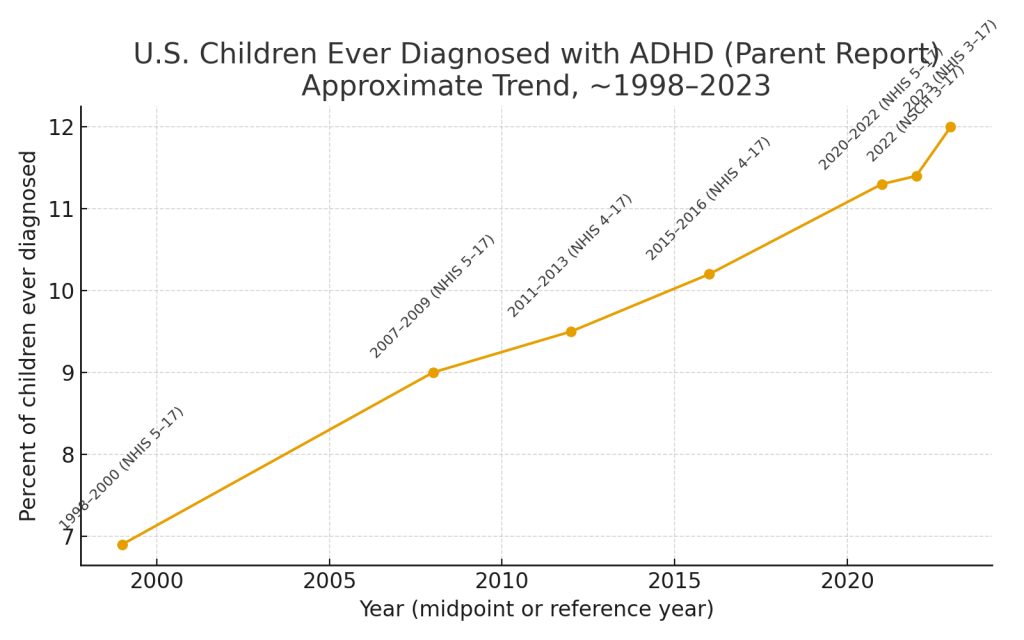

A particularly striking statistic is that 23% of boys are categorized as having a developmental disability. This label is almost statistically impossible. The deeper question is whether the educational system itself is maladapted to the developmental trajectory of boys. In other words, is it really the boys who are delayed, or the institutions failing to accommodate the normal variations in male development? Reeves and I share the sentiment that it is the educational system that is “delayed.” Developmental psychology shows that boys, on average, mature later in self-regulation, impulse control, and executive function. A rigid, one-size-fits-all educational model pathologizes these differences rather than supporting them.

I love the “redshirting” idea. Reeves’ practical recommendation that boys should be “redshirted”, or held back a year before starting school, aligns with this developmental reality. It recognizes that maturity is less about chronological age and more about calibrating behavior to fit social demands. Psychologist Erik Erikson once described adolescence as the crucible where identity and role confusion collide. Boys may simply need more time in that crucible, and institutions must adapt rather than expect conformity to artificially compressed timelines.

Social Decline and Family Instability

Beyond the classroom, Reeves highlights how boys and men are disproportionately harmed by family breakdown. In 1970, just 11% of births in the U.S. occurred outside of marriage. Today that number stands at 40%. The psychological consequences are profound. Children raised without stable father involvement face increased risks of behavioral problems, school failure, and emotional instability.

Importantly, Reeves distinguishes between race and gender in discussions of intergenerational mobility. While black and white women raised in poor families experience similar rates of upward intergenerational mobility, the same is not true for men. Revealing that the struggle is fundamentally male, and less racial. This observation forces a reframing of inequality. Many of the struggles chalked up to racial disparities are in fact gendered and disproportionately affect boys. The family unit, when fractured, appears to hit men the hardest, possibly because male identity is often more externally anchored, shaped by roles, responsibilities, and expectations that dissolve when fathers are absent.

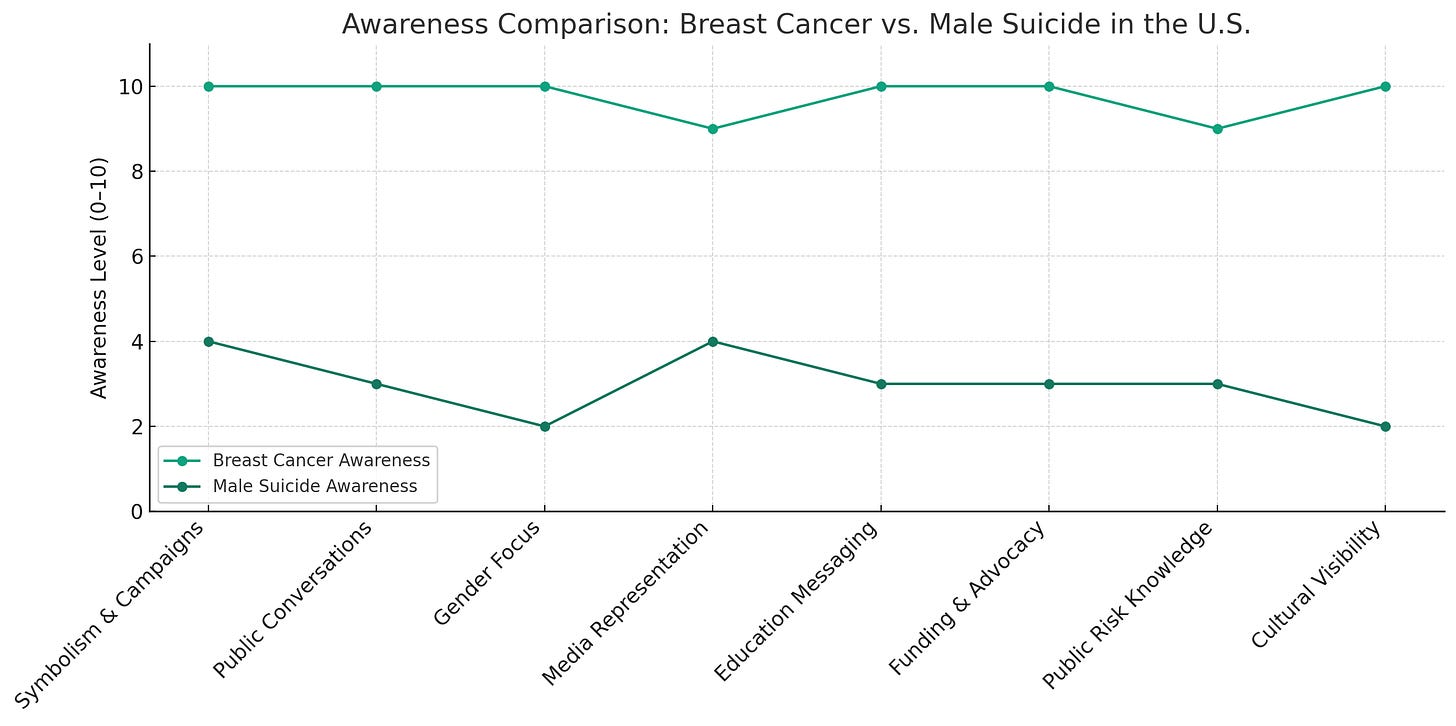

Despair, Suicide, and the Meaning Crisis

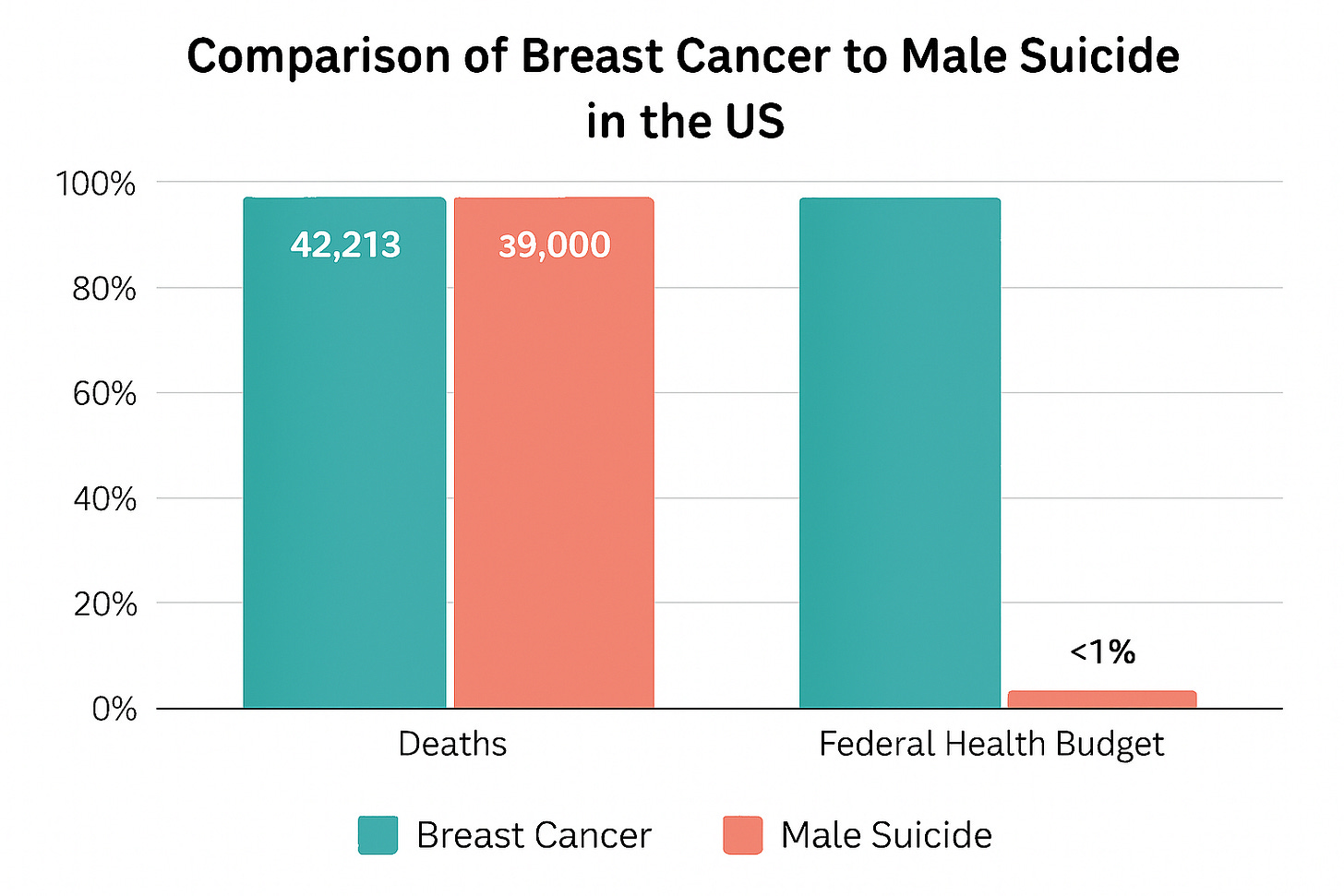

Perhaps the most chilling aspect of Reeves’ book is his treatment of despair. Male deaths from despair (suicide and overdose) are 3x higher than female. While male deaths from suicide alone are 4x hgher than female. Men account for 70% of opioid deaths in the United States. In suicide attempt notes, words like “useless” and “worthless” are repeated with haunting regularity. These are not just personal tragedies, they are societal symptoms.

Psychologically, despair emerges when meaning collapses. Viktor Frankl, the psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, argued that humans can endure almost any suffering if they retain a sense of purpose, echoing the sentiments of Nietzsche. Men who perceive themselves as unnecessary, whether socially, economically, or relationally, are particularly vulnerable. The erosion of traditional male roles (provider, protector, leader) leaves many men lost. Reeves’ book resonates as a warning. Neglecting the psychological needs of boys leads to men who no longer see themselves as essential to the fabric of society.

Biology, Masculinity, and the Politics of Pathology

Reeves is careful to address the biological underpinnings of masculinity. Testosterone, he notes, does not trigger aggression but amplifies it. This distinction matters. Aggression itself is not pathological. It is a natural drive that, when tempered, becomes assertiveness, competitiveness, and protective strength. The problem is not masculinity, per se, but the inability to regulate and channel masculine impulses into socially constructive forms.

Reeves criticizes the American Psychological Association (APA), which has published guidelines that largely ignore male realities while emphasizing female experiences. This reflects a broader cultural trend. Natural aspects of masculinity are pathologized, particularly on the political left, which often denies biological sex differences in favor of purely social explanations. From a psychological standpoint, denying biology is not only unscientific but harmful. To help boys and men, we must recognize their biological realities rather than pretending they do not exist.

Where Reeves Misses the Mark

While Reeves is strong in diagnosis, his prescriptions falter in later chapters. In his attempt to “balance” criticism between left and right, he ends up diminishing legitimate concerns. For instance, he offers a dismissive opinion of Jordan Peterson’s work on social hierarchies and gendered career preferences, despite strong empirical backing. He offers no empirical refutation. Only opinion.

Reeves suggests that men and women would choose diffrent careers if the stigma were deceased. His interpretation of the Su and Rounds1 study doesn’t hold up against other research. For instance, one study that shows that in more egalitarian societies, gender differences in occupational preferences actually widen.2 And another study that found that in very egalitarian communities, when controlling for education, occupational class position, age, social and family status, and income, differences among genders were vastly different.3 In other words, freedom reveals difference rather than erasing it.

Given the statistical likelihood of gender preferences in more egalitarian nations, we can’t dismiss this but maybe we can capitalize on the individuals in each gender that cease to represent the majority and lean on this faction to help close certain gender job-force gaps. Men high in neuroticism, who are also high in empathy, would do well in HEAL jobs. Like women who are more practical and less prone to neuroticism would do well in STEM jobs. Though the majority will not prefer these, those who will can help bring nuance to these occupations.

Reeves also entertains the idea of equality of outcome, which is an inherently socialist notion that undermines individual merit and autonomy. Quoting Margaret Mead as an authority on gender equality may not be the best idea, given that contemporary psychology and economics have moved far beyond Mead’s cultural anthropology. Equality of outcome is not only impractical but psychologically corrosive, as it requires group A remove something from group B without their consent, and give it to group C. That will never work in America.

The Role of Government: Help or Hindrance?

You already know the answer to this. But Reeves goes on to advocate for policy solutions such as legislating more male teachers and expanding paid parental leave. While well-intentioned, these proposals risk repeating the failures of affirmative action. Institutionalizing discrimination in the name of equity. Psychologically, boys need mentors and role models. Mandating male teachers through policy undermines organic, voluntary solutions. Similarly, paid leave initiatives, while attractive on the surface, raise serious economic questions. Reeves never explains how such programs would be sustainably funded, leaving taxpayers to shoulder the burden.

The deeper problem is that government has historically failed to solve cultural and psychological crises. The federal government will never be a viable solution to any problem in our country, outside of national security, federal banking, and housing the homeless. They have proven through history, time and again, to be the worst solution to any problem. The crisis of boys and men is rooted in family, community, and culture. These are arenas where government intervention tends to distort rather than heal. Psychologically, meaning is cultivated locally through fathers, teachers, mentors, and peers. Not bureaucratic decrees.

Toward a Psychological Renewal of Manhood

Despite disagreements, Reeves deserves recognition as one of the few public voices daring to raise the alarm about the plight of boys and men. He’s a pioneer. A revolutionary. His book contributes to a conversation that is long overdue. To move forward, psychology offers several points of guidance:

- Boys must be given time and space to mature without being pathologized.

- Masculinity must be acknowledged as biologically grounded and potentially virtuous, not inherently toxic.

- Family stability is critical. Without fathers, boys face developmental deficits that no government program can repair.

- Despair is not simply a matter of economics but of meaning. Men must be shown that they are needed.

Reeves reminds us that the boy is always present within the man. Psychological maturity means the boy is still alive within us but is no longer in charge. He’s tempered, integrated, and directed toward purpose. Our challenge, as a culture, is to stop treating that boy as defective and start guiding him toward manhood.

Conclusion

Reeves’ Of Boys and Men is a bold and necessary work, one that illuminates the depth of the male crisis with clarity and urgency. Where he falters is in solutions. Reeves too often yields to fashionable political narratives or relies on government prescriptions. But in identifying the problem, Reeves has accomplished something vital. He has given voice to the silent epidemic of male despair and decline. Psychologically, the task ahead is monumental. Create a society that nurtures boys into men who are not just functional but flourishing.

Stay Classy GP!

Grainger